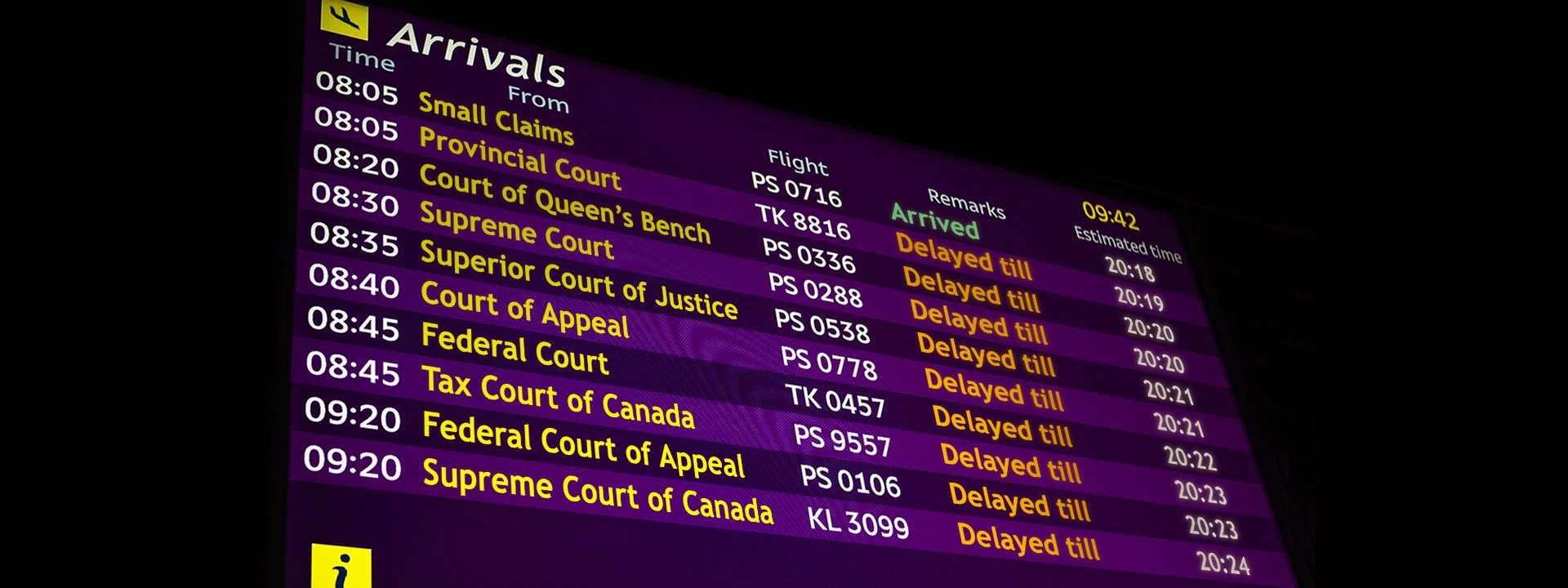

Does delay affect different groups in substantially different ways? If so, should constitutional guarantees of trial within “a reasonable time” result in different standards for different groups? The Supreme Court of Canada, in R. v. K.J.M., 2019 SCC 55 answered yes to the first question, putting significant emphasis on the subjective and practical experience of delay on young offenders. However, it answered no to the second question and declined to allow that differential experience of delay to support a different standard of timeliness.

The Court reaffirmed the importance of a time-limited constitutional rule for impermissible delay in the prosecution of criminal cases. It elected by a majority to uphold one rule for varying cases. In R. v. Jordan, the Supreme Court set out constitutional standards for impermissible delay in the prosecution of criminal cases beyond which would be presumptively unreasonable – 18 months for summary conviction offences and 30 months for indictable offences. In K.J.M. the Court revisited the Jordan standards in the context of prosecutions under the Youth Criminal Justice Act, the principal question being whether youth prosecutions would have the same time limits as laid out in Jordan, or be subject to stricter timeframes.

The judges all agreed that youth may suffer comparatively heavier consequences from delay.

However the majority declined to shorten the timeframes applicable to youth. Instead, the majority confirmed that the timeframes in Jordan applied to youth equally. While youth tend to suffer disproportionately from delay, the same could be said for many other groups, and an attempt to tailor the Jordan timeframes to the particular circumstances of every group would be unworkable:

[65] …. Jordan established a uniform set of ceilings that apply irrespective of the varying degrees of prejudice experienced by different groups and individuals. Setting new ceilings based on the notion that certain groups — such as young persons — experience heightened prejudice as a result of delay would undermine this uniformity and lead to a multiplicity of ceilings, each varying with the unique level of prejudice experienced by the particular category or subcategory of persons in question. Young persons in custody, young persons out of custody, adults in custody, adults out of custody, persons whose custody status changes, persons with strict bail conditions, persons with minimal bail conditions, persons who experience heightened memory loss, and others could all lay claim to their own distinct ceiling. Even within the category of young persons, this could lead to separate ceilings being established for different age groups: one for 17-year-olds, one for 14-year-olds, and so on. This would quickly become impracticable. Moreover, the result would be incompatible with the uniform-ceiling approach adopted in Jordan and would undermine its objective of simplifying and streamlining the s. 11 (b) framework.

The dissenters would have adjusted the constitutional protection in a manner that has regard to the particular characteristics of protected groups – in this case, youth. What is a reasonable period for an adult may be an unreasonable period for a youth – and, as a result, the Jordan timeframes should be shortened when dealing with youth.

The majority also held that the youthfulness of the accused is relevant to the determination of whether, despite falling under the Jordan ceiling of 18 months, a prosecution nevertheless took markedly longer than it reasonably ought. In that analysis, the age of the accused should be regarded as one of the “case-specific factors” to be considered.

The original case-specific factors listed in Jordan related mainly to the case and its handling, and did not specifically mention anything related to the offender:

The reasonable time requirements of a case derive from a variety of factors, including the complexity of the case, local considerations, and whether the Crown took reasonable steps to expedite the proceedings.

R. v. Jordan, [2016] 1 SCR 631, 2016 SCC 27 at ¶ 87

The broadening of what is considered relevant to timeliness is a welcome and important development. Looking solely at the complexity of a case or its legal aspects can only give us a limited understanding of timeliness. The personal characteristics of the parties often dictate whether a swift resolution is comparatively important. In the criminal context, it is not only the personal characteristics of the accused that are important, but also those of the victim.

Another welcome emphasis from the majority judgement is the necessity for all participants to seek timeliness and work cooperatively to achieve timeliness. Moldaver J. concludes:

[84] Stated succinctly, if we are to make the culture of complacency towards delay identified in Jordan a thing of the past, all criminal justice system participants must take a proactive and cooperative approach with a view to fulfilling s. 11 (b)’s important objectives (see Jordan, at para. 5). While this principle certainly applies in adult cases, it applies with even greater force in youth cases.

The choice of one period for a constitutional rule respecting delay has the advantage of certainty, although it has the disadvantage of overlooking very real differences in those affected. More profoundly the debate reflects the need to achieve timeliness as distinct from avoiding delay. However important avoiding delay is, it is not the only thing. Timeliness will mean different things for different types of cases and persons if it is to be real. K.J.M. demonstrates that saving people from the worst is not enough to achieve the full measure of timely justice.